Ansoff Matrix

What is the Ansoff Matrix? - By Tamizha Karthic

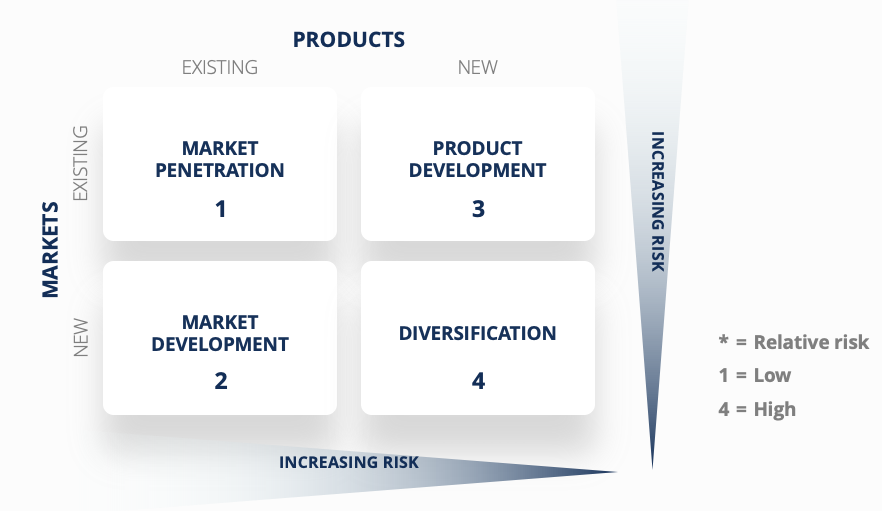

The Ansoff Matrix, often called the Product/Market Expansion Grid, is a two-by-two framework used by management teams and the analyst community to help plan and evaluate growth initiatives. In particular, the tool helps stakeholders conceptualize the level of risk associated with different growth strategies.

The matrix was developed by applied mathematician and business manager H. Igor Ansoff and was published in the Harvard Business Review in 1957. The Ansoff Matrix is often used in conjunction with other business and industry analysis tools, such as the PESTEL, SWOT, and Porter’s 5 Forces frameworks, to support more robust assessments of drivers of business growth.

Understanding the Ansoff Matrix

The Ansoff Matrix is a fundamental framework taught by business schools worldwide. It is a simple and intuitive way to visualize the levers a management team can pull when considering growth opportunities. It features Products on the X-axis and Markets on the Y-axis.

The concept of markets within the Ansoff framework can mean different things. For example, it could be a jurisdiction or geography (i.e., the North American market); it could also mean customer segments (i.e., target market/demographic).

The Matrix is used to evaluate the relative attractiveness of growth strategies that leverage both existing products and markets vs. new ones, as well as the level of risk associated with each.

Each box of the Matrix corresponds to a specific growth strategy. They are:

- Market Penetration – The concept of increasing sales of existing products into an existing market

- Market Development – Focuses on selling existing products into new markets

- Product Development – Focuses on introducing new products to an existing market

- Diversification – The concept of entering a new market with altogether new products

Market Penetration

The least risky, in relative terms, is market penetration.

When employing a market penetration strategy, management seeks to sell more of its existing products into markets that they’re familiar with and where they have existing relationships. Typical execution strategies include:

- Increasing marketing efforts or streamlining distribution processes

- Decreasing prices to attract new customers within the market segment

- Acquiring a competitor in the same market

Consider a consumer packaged goods business that sells into grocery chains. Management may seek greater penetration by amending pricing for a large chain in order to secure incremental shelf space not just for packaged food products but also for several lines of its pet food products, too.

Market Development

A market development strategy is the next least risky because it does not require significant investment in R&D or product development. Rather, it allows a management team to leverage existing products and take them to a different market. Approaches include:

- Catering to a different customer segment or target demographic

- Entering a new domestic market (regional expansion)

- Entering into a foreign market (international expansion)

An example is Lululemon; management made a decision to aggressively expand into the Asia Pacific market to sell its already very popular athleisure products. While building an advertising and logistics infrastructure in a foreign market inherently presents risks, it’s made less risky by virtue of the fact that they’re selling a product with a proven roadmap.

Product Development

A business that firmly has the ears of a particular market or target audience may look to expand its share of wallet from that customer base. Think of it as a play on brand loyalty, which may be achieved in a variety of ways, including:

- Investing in R&D to develop an altogether new product(s).

- Acquiring the rights to produce and sell another firm’s product(s).

- Creating a new offering by branding a white-label product that’s actually produced by a third party.

An example might be a beauty brand that produces and sells hair care products that are popular among women aged 28-35. In an effort to capitalize on the brand’s popularity and loyalty with this demographic, they invest heavily in the production of a new line of hair care products, hoping that the existing target market will adopt it.

Diversification

In relative terms, a diversification strategy is generally the highest risk endeavor; after all, both product development and market development are required. While it is the highest risk strategy, it can reap huge rewards – either by achieving altogether new revenue opportunities or by reducing a firm’s reliance on a single product/market fit (for whatever reason).

There are generally two types of diversification strategies that a management team might consider:

1. Related Diversification – Where there are potential synergies that can be realized between the existing business and the new product/market.

An example is a producer of leather shoes that decides to produce leather car seats. There are almost certainly synergies to be had in sourcing raw materials, although the product itself and the production process will require considerable investment in R&D and production.

2. Unrelated Diversification – Where it’s unlikely that any real synergies will be realized between the existing business and the new product/market.

Let’s work on the leather shoe producer example again. Consider if management wanted to reduce its overall reliance on the (highly cyclical) consumer discretionary high-end shoe business, they might invest heavily in a consumer packaged goods product in order to diversify.

Ansoff Matrix and Financial Analysis

It’s a common misconception that financial analysis is exclusively a quantitative exercise. And while it’s true that analysts must know how to make sense of assets and liabilities, dig through 10K filings, and build financial models, it’s also imperative that they understand the drivers of business growth, as these will inform a wide range of model assumptions.

The ability to translate qualitative findings from a SWOT or PESTEL analysis, an Ansoff Matrix, or a Porter’s 5 Forces framework into model assumptions is what sets world-class analysts apart from everyone else.

High-quality due diligence includes the ability to effectively model growth drivers, as these can have a profound impact on valuation estimates and important credit metrics.